About the artist

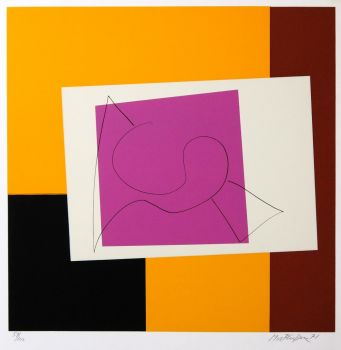

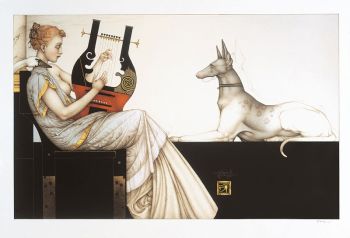

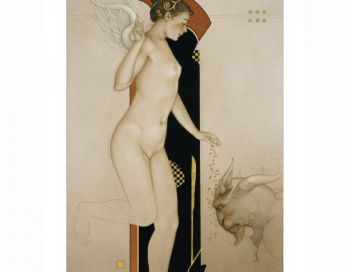

Allan D'Arcangelo was an American Artist and Printmaker, best known known for his paintings of highways and road signs. His reputation as a Pop artist was established in 1963 with his series of paintings of American highways and signs, an example of which includes US Highway 1, Number 5. A veteran of dozens of solo exhibitions beginning in the late 1950s. He taught Fine art at Cornell University, Brooklyn College, and the School of Visual Arts during the 1960s. He also taught painting in several other institutions throughout his career. During the early 1960’s, Allan D’Arcangelo was linked with Pop Art for example “Marilyn” (1962) and “Madonna and Child” (1963) “Marilyn” depicts an illustrative head and shoulders on which the facial features are marked by lettered slits to be “fitted” with the eyebrows, eyes, nose and mouth which appear off to the right in the composition. In “Madonna and Child,” the featureless faces of Jackie Kennedy and Caroline are ringed with haloes, enough for the period, to make their status as contemporary icons perfectly clear. D’Arcangelo is better known for his pictures of highways and roadblocks made during the 1960’s. The first of these pictured deep perspectival vistas in a simplified, flat plane, the view as seen from the driver’s seat as one zooms along the seemingly never-ending American highway in most any state. Next came a series “Barriers,” in which cropped, abstracted imagery of road barriers were superimposed over the one-point perspectival highway vistas. These were a move further towards concern with abstract, two-dimensionality without negating the element culled from seen aspects of the American landscape. The series called “Constellations” (there are 120 in all) further abstracted the view of road barriers into perspectival, jutting patterns thrusting across the canvas against a white ground. The element of the seen is never obliterated and always primary in D’Arcangelo’s dialectic, as amply evidenced in his return to highway imagery in the 1970’s. For several years during that decade, D’Arcangelo slowed down his formerly prolific output. In the Spring of 1982, he had his first one-man exhibition in New York in five years. The new pictures were rather scenic landscape vistas, simplified and showing his ongoing concern with jutting perspectival space, now inhabited by flatly painted images of highway overpasses, a jet wing, grain field, electric lines. Indications of the American industrial scene seem more related to the hand-painted, pristine look of Charles Sheeler than to the pop of, say, Roy Lichtenstein In form, there is also a reminiscence of field paintings in the simplicity and emblematic quality of these works. Now, as before, the main element in D’Arcangelo’s pictures is the post-abstraction search for, as he put it, “icons that matter,” monumental archetypes of the contemporary American expansive landscape highway. His paintings are in the permanent collections of the Tate Gallery in London, the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, the Denver Art Museum in Colorado, the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, the Butler Institute of American Art in Youngstown, Ohio, and many other public and private collections worldwide.